One from the Vault: INDIA AND U.S. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE COMPARED: SARBANES-OXLEY ACT’S EFFECT

April 3, 2021 | By Michael A. Harris

The following is a research essay written in 2005 by me when I was in law school. At the time I had been working in an immigration law firm as a clerk and had been working for a year in L-1 Visa petitions. Many of the clients I was working with were from India, and I started to learn how to read corporate records from India. So, when I took a course on Comparative Corporate Governance and was asked to pick a country and an area of its corporate laws, I selected India. What follows is the essay, without further updates, along with the presentation I gave to my class.

The rapid development of India’s corporate culture, which during the last 15 years “has been [a part of] the second fastest-growing country in the world,”[1] has been astonishing. It is predicted that its economic growth rate will increase even more in the next decade and will eventually be the fastest growing in the world.[2] A 2003 study by Goldman Sachs forecasts “that in 10 years India’s economy will be larger than Italy’s and in 15 years will have overtaken Britain’s. By 2040 it will boast the world’s third largest economy.”[3] What India is experiencing is perhaps more important to the United States than the threat of U.S. corporations moving overseas or outsourcing, as it presents an opportunity to observe a comparable corporate environment which is not very different from the U.S.

Increasing globalization or flattening of the world economy,[4] led by an evolving U.S. economy and the expanding availability of the Internet, has led countries such as India to emerge as new and rising leaders. The Republic of India has an estimated population of 1.1 billion people, more than 15 percent of the world’s population, with only China having more people. India is nearly three times the population size of the U.S., however only one-third the size geographically. India includes 28 states, 7 union territories and the National Capitol Territory (Delhi). Like the U.S., India has three branches of government – however its system is based on a British system inherited as a colony – and is based in federalism. Yet, the similarities end there since India’s federal government is allowed to exert much more control over its states than the U.S.[5]

India’s strong federal government allows it complete control over the formation and regulation of business entities. States, which do not set any rules for incorporating companies, have however become very powerful in their own legislation to lure in foreign companies. States, such as Karnataka, which contains the major city of Bangalore, have shown the ability to regulate other areas of corporate life, such as in tax relief, labor requirements, and other industry specific codes.[6] Karnataka alone “houses 65 of worlds fortune 500 companies.”[7] However, reforms by the central government are the direct reason for India’s economic growth.

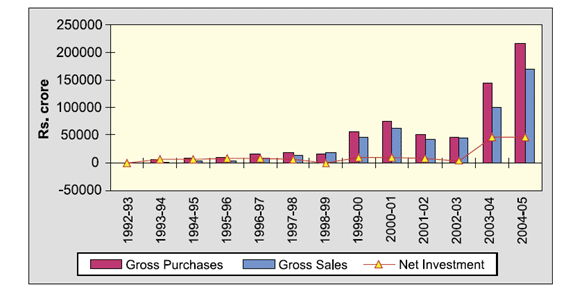

In 1991, India made reforms to its investment and security exchange markets, as well as to other restricted trade and financial areas.[8] One of these apparent changes took effect in 1992 when foreign institutional investors were permitted to invest in Indian securities.[9] After September 11, President Bush ended U.S.-imposed sanctions against India for its 1998 Nuclear Tests, which had stopped millions of dollars in economic aid, including funding for the development of India’s securities stock market.[10] Yet, ironically, this did not immensely hurt India because in 1998 India’s foreign capital investment began to skyrocket. Furthermore, India witnessed even greater foreign investment after the removal of U.S. sanctions, most notably after the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) and in a post-Enron era (See Figure 1). Today, the U.S. ranks as “India’s largest trading”, and its “largest investment partner, with a 17% share”.[11] As India continues to grow, in population and economically, its young workforce will continue to spur development.[12] Thus, the more the U.S. understands the reasons for India’s growth, such as through a comparison of both countries’ corporate and market responses to elements of change (i.e. the Enron Scandal and SOX), the better equipped the U.S. will be to adapt its current law.

I. U.S. Outsourcing: Trends and Statistics Involving India

As a result of India’s favored status in the world, it has risen to become the largest supplier in the world of outsourced employment to foreign corporations.[13] In 2005, the total value of outsourcing to India was “estimated at $17.2 billion or 44 percent of the worldwide total, according to a report from India’s National Association of Software and Service Companies (NASSCOM).[14] … About 80 percent of the Fortune 500 companies outsourced at least one operation to India in 2004, compared with 60 percent in 2003, added the report.” NASSCOM’s Chairman, S. Ramadorai, predicts “India’s market share to expand to 51 percent by March 2008…”[15] And furthermore, the Associated Press points out that this market trend has likely been influenced because India’s salary “for software development workers ranges between $18 and $26 [per hour]… compared with $55 to $65 per hour in the United States and Europe.”[16] Currently, India’s largest outsourcing competitors are Canada (32 percent market share), China (4.9 percent), and Eastern European countries (4.5 percent).[17]

Some of India’s largest outsourced products are software development, services in customer phone communications, and manufacturing.[18] In a report issued to President Bush by the CEOs of 5 U.S. corporations and 10 of India’s largest corporations, it was stated that more substantial U.S. investment in India would “help upgrade its low-cost manufacturing.”[19] Yet, increased U.S. investment is on the way, as companies such as Cisco Systems, the largest computer network manufacturer, will “invest $1.16 billion in India, tripling its work force [in India], and companies like Intel and Microsoft [have] swiftly [responded]… with commitments of their own.”[20] Cisco’s CEO has stated India’s market potential may allow it to be Cisco’s largest Asian market in five years.[21] President Bush’s suggestion that the American and Indian CEOs put forth a report on corporate development between the two countries is proof “‘that Indian and U.S. businesses are catalysts for a close relationship between the two countries.’”[22]

II. Summary of the History of Corporate Law in India

A. The Effect of Colonial History on Corporate India.

India is a country of many various cultures, with 17 major languages, and is the world’s largest democracy. It has fought to attain this distinction. European presence in India dates to the seventeenth century, and in 1757 the British won political control over India.[23] Before India’s independence from Britain in 1947, much of India’s industrial development was heavily restricted by British economic policies.[24] From 1950 to 1951, there were individuals who held “multiple directorships and extensive interlocking directorships among both Indian and British firms.”[25] A study conducted during this period revealed “nine leading Indian industrial families held nearly 600 directorships or partnerships in Indian industry”.[26] Following the recommendations of a Company Law Committee formed in 1950, India passed a revised Companies Act in 1956, based upon the history of the many acts passed since 1908 which attempted to regulate companies.[27] Since this time the Companies Act has been amended as many as 24 times, including major amendments in 1988 and 2002, however the 1956 Act remains the basis for enforcement of business entities.[28]

Post-colonial India has gone through phases of severe isolationism, socialist movements, and major wars (notably with Pakistan, which was formed in 1947 when India was split in two). India currently has some of the world’s largest concentrations of poor. It is a country which may contain “several Silicon Valleys, but it also has three Nigerias within it, more than 300 million people living on less than a dollar a day.”[29] However, its middle class contains just as many people and is growing strong.[30] India has thus emerged, with a law deep rooted in English common law, and an experience similar to the U.S.

B. Corporate Reforms in India.

In 2003, in response to U.S. corporate scandals and legal developments such as Sarbanes-Oxley in the U.S. and the European Union Auditing Directive, India’s Ministry of Company Affairs created the National Foundation for Corporate Governance (NFCG), a non-profit organization.[31] Then in 2003, the Ministry of Company Affairs passed an amendment to the Companies Act which created new laws for “[1] independence of auditors, [2] relationship of auditors with the management of the company, and [3] independent directors with a view to improve the corporate governance practices in the corporate sector.”[32] In 2003, after the above amendment and further study of Sarbanes-Oxley, the Indian Government proposed more changes to the law and began to draft many recommendations.[33]

In 2004, responding to changes to its law the previous year, the Government of India published a Concept Paper on Company Law (what U.S. regulatory agencies would call a proposal for new regulation and comment) in an effort to further reform its laws. The Concept Paper sought to make changes to the following areas:

- Formation of company and other organizational matters

- Accounts and Audit

- Management of the company

- Powers of Central Government to carry out inspection and investigation of companies

- Reorganization of companies by merger, consolidation, etc.

- Winding up companies

- Other business entities which may register

- Producer Companies, a separate class of companies

- Foreign companies, offenses and penalties and other miscellaneous provisions[34]

Ultimately, these reforms were trumped by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), when it promulgated its Clause 49 regulation before the Companies Act amendments could take place. Experts state that the SEBI agency initiative to take the lead in this area of corporate governance is a better option because it was feared more “red tape” would emerge from a new consolidation of Companies Act law.[35]

C. Current Corporation Law in India.

According to the Ministry of Company Affairs guidelines, registration requirements to incorporate a new company include: (1) Memorandum and Articles of Association, (2) Declaration of compliance, (3) Notice of registered office of the company, (4) Names of Director, Manager or Secretary.[36] These rules are very similar to the general requirements to incorporate in most states in the U.S. However, because India’s central government has complete power it also has eliminated the “race to the bottom” inclusive in many U.S. incorporate schemes. Such as India’s regulation of Shareholder Voting Rights: “according to Indian rules and regulations, all shareholders have the right to participate and vote at general meetings.”[37] In India, when someone acquires “more than 15 percent of shares or voting rights requires the acquirer [must] make a public stock offering and to approve a merger…[and] regulations require a shareholder vote of 75 percent.” [38] The Companies Act requires that an Annual General Meeting (AGM) “be held every year, and that a notice convening the meeting be sent to all shareholders at least 21 days in advance of the meeting. In addition to the AGM, the Companies Act allows for shareholders controlling 10 percent of voting rights or paid-up capital to call a special or Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM).”[39] Without a powerful centralized government, shareholder rights would vary across the country.

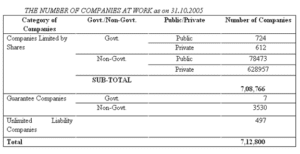

As of October 2005, there were nearly 80,000 non-governmental public companies actively registered in India (See Figure 2). In terms of private companies, over 600,000 are currently active and registered. For Indian companies that wish to do business outside of the country, the impetus for ascribing to new regulatory requirements is not their own law, but rather the effects of a global market.[40] This type of voluntary compliance is largely seen as a result due to corporate governance trends aimed at furthering worldwide attempts to become more transparent. Another reason for this voluntary movement in India is also likely due to its slow judicial system, which can take 10 to 20 years to render a verdict in corporate law.[41] This is certainly demonstrates one clear benefit of having each state in the U.S. administer its own corporate law. States such as Delaware, which comprises a great volume of corporate history, have made this easy. Thus, with the development of Sarbanes-Oxley—a law passed by the federal government—it must be asked if the U.S. is moving towards a corporate system which will have state courts interpreting federal law. Furthermore, is this type of system also being developed in India? That is, is India experiencing the growth of a corporate system that is regulated by the federal government in conjunction with the states, or without any state influence.

III. Summary of U.S. Corporate Law Regarding Sarbanes-Oxley

A. Overview of Sarbanes-Oxley

A significant result of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) was the implementation of an Accounting Oversight Board to oversee audits of public companies subject to U.S. securities laws. The board was implemented “to be a private non-profit organization to oversee public company audits and ‘further the public interest in the preparation of informative, accurate, and independent audit reports.”[42] Section 301 of the Act directs the SEC to require any company listed on a U.S. Stock Exchanges to have an audit committee “comprised of independent board members that is directly responsible for the appointment, compensation and oversight of auditors….”[43] Section 407 also has an additional requirement that “at least one audit committee member as a “financial expert” with experience in U.S. GAAP [Generally Accepted Accounting Principles in the United States], or to disclose the reasons why there is no such “financial expert” serving on the audit committee.”[44] Section 302 specifies that each CEO and CFO must certify in every quarterly and annual report that “there is nothing misleading contained therein… [and] that particular internal controls have been put into place at their company to ensure that all material information would be made known to that officer”[45]. Section 402 bars public companies “to extend or maintain credit or make loans to directors and executive officers”.[46]

Section 404 Costs: Companies are mandated to make reports “on the effectiveness of its internal controls over financial reporting and the accompanying certifications will subject the company and its senior officers to potential civil and criminal liability if false.”[47] CEOs and CFOs face $1 million in fine and or jail for mistakes, which include failing to “assert in its report whether effective controls exist, identifying what framework management used to design and test the effectiveness” and not reporting “[material] changes to controls and any material weaknesses…[which] the outside auditors must [also] attest and opine as to statements made by management.”[48]

Section 406 requires a public company to disclose under the SEC’s Securities Exchange Act Rules if a code of ethics has been adopted for senior financial officers or an explanation of its failure to adopt such a code.[49] Section 906 provides criminal penalties will be imposed on “anyone who willfully and/or knowingly violates these certification provisions.”[50] However, due to a knowledge requirement, potential plaintiffs will have to prove that corporate officers had actual knowledge they were falsifying documents.[51] Thus, according to the current President & CEO of NASDAQ, “SOX has had the unintended consequence of triggering a ‘race to the bottom’ by stock markets and companies seeking advantage via less jeopardy, less regulation, less cost and less hassle.”[52]

B. How to Reform SOX?

In 2005, an Oversight Systems Financial Executive Report on SOX conducted a survey of over 200 “financial executives and found a significant majority believe that, after implementing [SOX control] requirements” very little has proven beneficial.[53] Almost one-half of those surveyed, “SOX compliance resulted in reduced risk of fraud and errors, and they now have more efficient operations.”[54] Additionally, an Ernst & Young survey made in 2005 revealed that “87%…noted enhanced accountability and ownership of controls”.[55] According to former SEC Chairman Harvey Pitt: “SOX has certainly and substantially increased corporate-compliance costs.”[56]

SOX has been beneficial to thwarting corruption in corporate America. However, the true benefits will be determined in the future, mostly because of a new race to privatization.[57] The largest obstacle for public companies that attempt to implement SOX has been Section 404 Costs.[58] The Wall Street Journal has said that “90 percent of international small companies intending to go public are choosing to list abroad because of SOX costs and concerns.”[59] The SEC’s Advisory Committee on Smaller Public Companies states that there should be “an exemption from Section 404 for companies with less than $128 million in market cap and revenues under $125 million … [and partial exemption for companies] with up to $787 million in market cap, as long as they had revenues less than $250 million”.[60] If these exemption were in place, the SEC Committee states “exempted [companies] would account for only 6% of U.S. market cap, which means Section 404 would still apply fully to 94% of equity market capitalization.”[61]

After SOX’s passage, statistics show that public U.S. companies increasingly are returning to a private status. In the first eight months of 2003, “‘sixty public companies had already [gone] private … up from forty-nine during the same period in 2002 and thirty-two in 2001.’ … The number of companies going private in the sixteen-month period following the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act numbered 120, 30 percent more than in the sixteen-month period prior to its July 30, 2002 enactment.”[62] SOX has also made it very difficult for international companies that attempt to exist publicly,[63] “[the] strict requirements of section 301…are ill suited for, and in some cases actually conflict with, the home country laws of many foreign [companies].”[64]

IV. India’s Corporate Law Version of “Sarbanes-Oxley” and related provisions

A. Overview

India has two places in its legal system where a “Sarbanes-Oxley” (SOX) type of law appears: (1) Companies Act and (2) Clause 49, a regulation for listed companies made by India’s securities exchange commission, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). In 2002, SEBI revised its requirements for listed public companies “with Clause 49, [with] mandatory and non-mandatory corporate governance provisions.”[65] After the institution of SOX, the requirements for listed public companies “again changed in 2004 to incorporate” what SEBI believed were the best provisions of SOX.[66] The Ministry of Company Affairs is responsible for enforcing all provisions of SOX-type laws which fall under its purview. SEBI’s 2004 reforms took effect on January 1, 2006, and like SOX it sought “greater transparency in the way Indian companies do business.”[67]

B. Fundamental Characteristics of India’s SOX Laws: Board of Directors.

Unlike in the U.S. under SOX, which requires a separate audit board committee, in India the SEBI Commission only requires that company boards be partially independent. SEBI’s Clause 49 requires “that at least one-third of the board be non-executive and that a majority of these be independent.”[68] Clause 49 additionally specifies that …[when] the chairman of the board is an executive, 50 percent of the board [must] be comprised of independent directors.”[69] Board independence is limited by the number of independent directors in India.[70] However the Companies Act requires less, specifying “that 33 percent of board members or two members, whichever is greater, be present…and [there] is no provision that specifies whether non-executive or independent members need be present.”[71] Under the Companies Act and Clause 49, an independent director is “a non-executive director who:

(i) aside from director’s remuneration, does not have any material pecuniary relationship or transactions with the company

(ii) is not related to the promoter or a person in management on the board or one level below the board,

(iii) has not been an executive for the past three years,

(iv) is not or has not been a partner in the past three years of a statutory or internal audit firm or a firm providing consulting services to the company,

(v) is not a material supplier, service provider or customer or a lessor or lessee of the company which may affect independence of the director,

(vi) is not a substantial (owning 2% or more of voting rights) shareholder of the company.”[72]

In addition to India’s requirements for independent board directors, it has been suggested that it make further reforms, such as “Increased autonomy for management… [independent] board-level nomination committees to appoint directors…[reduced] interference from sector Ministers…[and] a [focus] on profitability by linking senior management compensation to performance”.[73]

C. Fundamental Characteristics of India’s SOX Laws: Penalties

Perhaps contrary to Sarbanes-Oxley, Clause 49 penalties do not appear to be strongly enforced. Its harshest penalty for not adhering to requirements is a company’s delisting as a sellable security.[74] However, because India fails to regularly de-list a company, due to SEBI’s fears that it would negatively impact minority shareholders “by taking away their ability to exit equity markets,”[75] Clause 49 is proving difficult to comply with. Due to this lack of enforcement, 20 percent of the companies listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange (one of India’s two largest securities trading markets), or over 1,000 companies, are not in compliance.[76] Despite that this 20 percent only symbolizes fewer “than 5 percent of total market capitalization and have little or no trading volume, the reluctance of regulators to take action against errant companies raises concerns regarding the enforcement and surveillance mechanisms in the country.”[77] However, while Clause 49 is still a work-in-progress, it still demonstrates that India will continue to reform.[78]

D. Effects of Clause 49: Rush Back to Privatization? Trends in Foreign Institutional Investors in India.

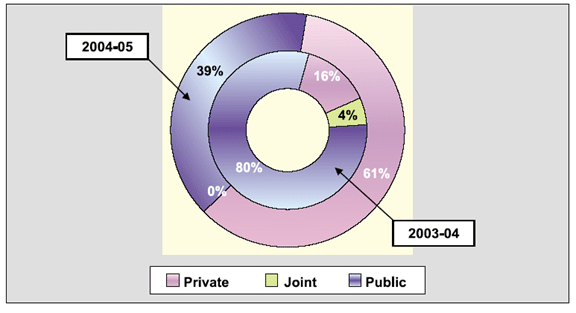

As has been illustrated by growing trend of U.S. public companies returning back to a private status, the same might be said of Indian public companies. India has the largest number of publicly listed companies in the world, as demonstrated by Figure 2, below. Additionally, since the imminent introduction of Clause 49 in 2004, the presence of Sarbanes-Oxley and other influential corporate scandals in the U.S., just during these two time periods (from 2003-2004 and 2004-2005) India has witnessed an unusual trend in the listing of companies. According to SEBI, 2004-2005 saw a decrease in publicly listed company capitalization from 80 percent to 39 percent (See Figure 3). As well, 2004-2005 saw an increase of privately listed companies increasing from 16 percent to 61 percent. No joint listings existed in 2004-2005, down from 4 percent in 2003-2004. Why this has occurred may lead to speculation, however it at least shows that the corporate mindset in India is favored towards privatization. Thus, a rush back to privatization—as many smaller companies in the U.S. are doing in order to avoid the crux of Sarbanes-Oxley—is also apparent in India in order to avoid Clause 49.

V. Conclusion

India is very much an independent country, yet it will model itself after the reforms and lessons of other countries. This is so despite the government’s National Foundation for Corporate Governance adherence to Sir Adrian Cadbury’s statement[79] that

A code of corporate governance cannot be imported from outside, it has to be developed based on the country’s experience. There cannot be any compulsion on the corporate sector to follow a particular code. An equilibrium should be struck so that corporate governance is not achieved at the cost of the growth of the corporate sector.

It seems likely that India may take a course similar to where the U.S. may be headed. Diverting the costs associated with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act’s Section 404 appears to be a growing call for reform. Likewise, in India reform may be needed on a similar basis, using an exemption based on market cap thresholds. Without such reform, India may face increasing difficulty, based on a “rough estimates [that]…the top 500 listed companies, with an average of nine members on their boards, will need to find 2,500 new board members.”[80]

Despite the rush to privatization, in the U.S. and India, it must be noted that it may only be a temporary trend. Both countries will likely see an eventual re-stabilization of public company listings. In India, the more “foreign direct investment [that] flows to India [continues], [the more] medium-sized Indian companies should be more willing to

embrace better practices to gain access to foreign capital.”[81] Companies will raise more capital through a public listing, and its lure should better corporate transparency in India. India’s lesson—with its voluminous amount of actively listed companies—should demonstrate an eventual compromise in the development of the United States’ continued reform of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and its intrusion into state corporate law.

Figure Charts & Graphs

Figure 1. Foreign Institutional Investment, 2004-2005. Securities & Exchange Board of India (SEBI), Annual Report 2004-2005: PART TWO: REVIEW OF TRENDS AND OPERATIONS, p. 38. Located at http://www.sebi.gov.in/annualreport/0405/Part2.pdf.

Figure 2. Ministry of Company Affairs, Government of India. GROWTH OF CORPORATE SECTOR DURING OCT. 2005. http://www.mca.gov.in/ MinistryWebsite/dca/corporategrowth/growth.html.

Figure 3. Sector Shares in Total Resource Mobilization 2004-2005. Securities & Exchange Board of India (SEBI), Annual Report 2004-2005: PART TWO: REVIEW OF TRENDS AND OPERATIONS, p. 3. Located at http://www.sebi.gov.in/ annualreport/0405/Part2.pdf.

[1] Newsweek, “India Rising”, Fareed Zakaria, March 6, 2006, p. 34.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] See Thomas L. Friedman. The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005.

[5] U.S. Department of State, Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs, December 2005 Background Notes, Located at http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/3454.htm.

[6] See Karnataka’s Government Website at http://www.karnataka.gov.in.

[7] See the Government of India’s “Know India” website, located at: http://www.india.gov.in/knowindia /st_karnataka.php.

[8] U.S. Dept of State (Note 5)

[9] Securities & Exchange Board of India (SEBI), Annual Report 2004-2005: PART TWO: REVIEW OF TRENDS AND OPERATIONS, p. 37. Located at http://www.sebi.gov.in/annualreport/0405/Part2.pdf.

[10] U.S. Dept of State (Note 5); and “What the sanctions are and what they mean”. The Statesman (India). May 14, 1998.

[11] U.S. Dept of State (Note 5)

[12] Newsweek, “India Rising”, which notes that India will have the fastest growing economy in the world “over the next 50 years…because its work force will not age as fast as others”, p. 34.

[13] Id.

[14] CFO.com, “India Still No. 1 Outsourcing Haven”, Stephen Taub, June 3, 2005. Located at http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/4050685/c_4050702

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Saritha Rai, The New York Times, “Executives See U.S. Link as Crucial in India’s Growth”, March 3, 2006.

[19] Id.

[20] Id.

[21] Id.

[22] Id.

[23] U.S. Dept of State (Note 5).

[24] Ananya Mukherjee Reed; Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, York University, Toronto. Perspectives on the Indian Corporate Economy: Exploring the Paradox of Profits, St. Martin’s Press (Palgrave), 2001, p. 91.

[25] Id at p. 83.

[26] Id.

[27] Id. at pp. 83-98.

[28] Ministry of Company Affairs, Government of India. Concept Paper on Companies Bill 2004, p. 1, Located at http://www.mca.gov.in/MinistryWebsite/dca/common/conceptpaper.pdf.

[29] Newsweek, “India Rising”(See Note 12).

[30] Id.

[31] Ministry of Company Affairs, Government of India. Annual Report of the Ministry of Company Affairs 2004-2005, Chapter 1, p. 5. Located at http://www.mca.gov.in/MinistryWebsite/dca/report/ annualreport2005/annualreport2005.html.

[32] See Note 28, Concept Paper, p. 1.

[33] Ministry of Company Affairs High Committee, Government of India, Recommendations of the Naresh Chandra Committee Report on Corporate Audit and Governance (2002), Executive Summary. Located at http://www.nfcgindia.org/library.htm.

[34] See Note 27, Concept Paper, p. 1.

[35] Institute of International Finance, Inc., Task Force Report, February 2006. Corporate Governance in India: An Investor Perspective, p. 6. Located at http://www.iif.com/data/public/ IIFCorpGovIndia_0206.pdf.

[36] Ministry of Company Affairs, Government of India, Website located at http://www.mca.gov.in/ MinistryWebsite/dca/guidelines/guidelines.html.

[37] Institute of International Finance at p. 13 (See Note 35).

[38] Id. at p. 14.

[39] Id. at p. 15.

[40] Id. at p. 7.

[41] Id. at p. 10.

[42] Joseph F. Morrissey, Visiting Assistant Professor of Law Chicago-Kent College of Law. Columbia Business Law Review, “Catching the Culprits: Is Sarbanes-Oxley Enough?”, 2003 COLUM. BUS. L. REV. 801, 837-38.

[43] Kenji Taneda. Columbia Business Law Review, “SARBANES-OXLEY, FOREIGN ISSUERS AND UNITED STATES SECURITIES REGULATION”, 2003 COLUM. BUS. L. REV. 715, 738.

[44] Id. at 738-39.

[45] Morrissey at 841 (See Note 42).

[46] Taneda at 743 (See Note 43).

[47] CIO.com, “Ask the Expert”, Deborah Birnbach. Located at http://www2.cio.com/ask/expert/ 2004/questions/question1918.html.

[48] Id.

[49] Tony A. Paredes, Associate Professor of Law, Washington Univ. School of Law. “Enron: The Board, Corporate Governance, and Some Thoughts on the Role of Congress”, Enron: Corporate Fiascos and Legal Implications, p. 517.

[50] Morrissey at 842 (See Note 42).

[51] Id.

[52] Bob Greenfield, president and CEO of NASDAQ, The Wall Street Journal, “It’s Time to Pull Up Our SOX”, March 6, 2006; Page A14.

[53] Harvey L. Pitt, Former SEC Chairman, Forbes Magazine, “Trials And Tribulations Of Enron And S-Ox”, Located at http://www.forbes.com/columnists/2006/01/20/enron-sarbox-pitt-commentary-cx_hlp_0123harveypitt.html.

[54] Id.

[55] Id.

[56] Id.

[57] Joshua M. Koenig, Columbia Business Law Review, “A BRIEF ROADMAP TO GOING PRIVATE”, 2004 COLUM. BUS. L. REV. 505, 506.

[58] Greenfield (See Note 52).

[59] Id.

[60] Id.

[61] Id.

[62] Koenig at 506 (See Note 57).

[63] Taneda at 736 (See Note 42).

[64] Id. at 739.

[65] Institute of International Finance, Inc. at p. 6 (see Note 35).

[66] Id.

[67] Wharton School Publishing, “Is Indian Business Ready for a Brave New World of Tough Corporate Governance?”, Located at http://www.whartonsp.com/articles/printerfriendly.asp?p=433384.

[68] Institute of International Finance, Inc. at p. 16 (see Note 35).

[69] Id.

[70] Id.

[71] Id.

[72] Id. at p. 22.

[73] Id. at p. 8.

[74] Id. at p. 6.

[75] Id.

[76] Id.

[77] Id.

[78] See Sahad P.V. Business Today. “Accounting standards are converging rapidly”, April 24, 2005, Comments by James S. Turley, CEO of Ernst & Young, who also states that “India and China are going to be the biggest economies in the world. So we want to make sure that we are leaders here and keep that position for the next five, 10, or 20 years.”

[79] National Foundation for Corporate Governance. “Discussion Paper: Corporate Governance in India: Theory and Practice”, February 2004, Section 4, p. 9. Located at http://www.nfcgindia.org /library/cgitp.pdf.

[80] Wharton School Publishing (See Note 67).

[81] Institute of International Finance (See Note 34).